Two Cents is an original column akin to a book club for films. The Cinapse team will program films and contribute our best, most insightful, or most creative thoughts on each film using a maximum of 200 words each. Guest writers and fan comments are encouraged, as are suggestions for future entries to the column. Join us as we share our two cents on films we love, films we are curious about, and films we believe merit some discussion.

The Pick

An unfinished film about an unfinished film, The Other Side of the Wind has long tormented film fans as a tantalizingly close but never realized almost. Orson Welles conceived of the film in 1961 following the death of Ernest Hemingway, inspiring Welles for a story about a similarly man’s-man film director who reaches the end of their days desperate and alone.

Welles also conceived of an innovative way to shoot the story, utilizing multiple film stocks and cameras to capture a faux-documentary aesthetic. The film would follow aging director J.J. “Jake” Hannaford (the legendary John Huston) on the last day of his life as he invites hordes of press, friends, and industry luminaries to his house so he can show a rough cut of his new film, titled, of course, The Other Side of the Wind.

Shot piecemeal (as was customary for Welles during the latter, financially-strapped segment of his career), The Other Side of the Wind was assembled over a period of years, with Welles sometimes shooting one person’s half of a conversation a full four years before bringing in Huston for the conversation’s other half. Tax troubles and money woes kept stalling out production, with Welles often having to resort to trickery (read: flat out criminal lying) to grease wheels and keep things moving.

Welles would eventually succeed in editing together 40 minutes of completed film, but legal and financial woes forbid its completion. Welles passed away in 1985, seemingly leaving the film to be one more frustrating ‘almost’ in the career of the ever-cursed auteur, alongside the likes of his unfinished Don Quixote and his vanished Merchant of Venice. But through the valiant efforts of producers and film historians, The Other Side of the Wind was eventually freed from the morass and edited to something like completion in accordance with notes and guidance left by Welles.

The completed The Other Side of the Wind played at festivals before finally being distributed by Netflix, receiving both accolades and dismissal from audiences. We put it to the Two Cents team to decided whether this was one lost film that should never have been found. — Brendan

Next Week’s Pick:

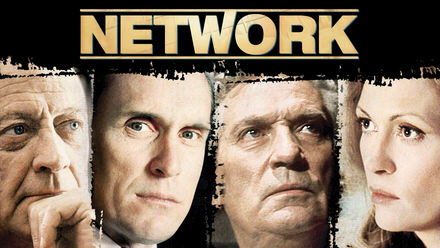

We’re mad as hell, and we’re not going to take it anymore. Powerful and damning, Network is writer Paddy Chayefsky and director Sidney Lumet’s scathing analysis of the intersection of news and entertainment. — Austin

Would you like to be a guest in next week’s Two Cents column? Simply watch and send your under-200-word review on any MCU film to twocents(at)cinapse.co anytime before midnight on Thursday!

Our Guests

Full disclosure: I saw a big chunk of Other Side of the Wind years ago at a Welles event while at NYU. What I saw then was rough, unedited, and not very good. The assembled version released on Netflix this year has been edited into a mostly coherent narrative, but it’s still rough and still not very good. Movies about directors are a tried and true genre in filmmaking, both Hollywood and otherwise. But I would much rather watch 8 1/2, Day for Night, All That Jazz, or even Contempt again than revisit The Other Side of the Wind. The film’s faux documentary format seems designed to conceal (or at least excuse) its sporadic, troubled production. Instead it leads to sluggish and disjointed pacing, and it makes an already meandering narrative feel even longer. On top of that, the film-within-a-film is laughably bad and works primarily as an excuse to show off Oja Kodar’s body as often as possible. I’ve heard it suggested that what I see as flaws are in fact deliberate choices; both the film and the film-within-a-film are a kind of parody of the sort of films I listed above. If that is the case, it’s not very funny and any potential for satire is mostly weighed down by its own self-importance. Also, just as an aside, I am endlessly creeped out by older directors who go out of their way to get their wives/girlfriends/lovers naked on film.

The cast is mostly good. John Huston is alternately charismatic and disturbing as the main character — but we never get much more than a superficial sense of who he is. Peter Bogdanovich is surprisingly good as one of Huston’s protégés, and often his performance alongside Huston’s are the only things giving the film any sense of momentum. I’m glad this film exists even as an approximation of what Welles’ version might have been. But ultimately I don’t think any potential editing or reworking could have made this into a “good” movie.The Other Side of the Wind goes through the motions of exploring the life of a director near the end of his career, but is unwilling or unable to offer anything like insight into the character or his creative process. (@T_Lawson)

The Team

You know, if it wasn’t for the existence of F for Fake, I might have more patience with The Other Side of the Wind. Were it not for that 1975 Orson Welles film, I might be willing to appreciate Wind as an experimental effort, a noble attempt to grapple with a new format and style. Heck, just because an experiment is a failure doesn’t mean the experiment wasn’t worth the effort.

Unfortunately, F for Fake does exist, and it is so much exponentially better that I can’t even shrug at Wind as a misbegotten attempt. F for Fake plays with image and form just as much as this film, but with a palpable sense of play, and fun,a trickster delighting in showing you the trick, while still tricking you. Here, I couldn’t tell you what the mockumentary approach adds or how it enhances the story of a doomed director grappling with a doomed film.

The problem is, that story isn’t at all engaging. Huston is a magnetic film presence, but J.J. Hannaford is a miserable, uninteresting caricature of an over-the-hill bastard, and none of the circle of grotesques that surround him are all that compelling either. It doesn’t help that the film-within-the-film is a laughably terrible parody of then-contemporary European art films, which just makes all the bad behavior and misery even less justifiable. When you factor in the massive doses of misogyny and homophobia, the resultant stew is near-choked on misanthropy and more or less useless beyond as a historical relic of an ugly moment in Hollywood, and a low moment for a master. (@theTrueBrendanF)

I’m sure there will be those who will slam The Other Side of the Wind as one of the most up front criticisms of Hollywood ever put to film. Not only does Welles illustrate his evaluation of the industry through the director’s struggle to maintain creative freedom in the face of studio battles and almost mind-numbing adoration, but also in the array of thinly-veiled versions of real-life people who have been turned into characters for the film. Among those supposedly ripe for cinematic reinvention are the likes of critic Pauline Kael, studio executive Robert Evans and legendary actress Marlene Dietrich. No one gets a more “on the nose” treatment however than Bogdanovich’s hot shot director who is forever entranced by the glow of his mentor’s legacy.

Beyond the individual send ups, The Other Side of the Wind takes on the state of the movie industry itself through a collection of raw footage showing prominent names of the day including Henry Jaglom and Dennis Hopper discussing their craft in relation to self and society, echoing the strong self-analytical quality running rampant in the era of the great auteur. With sequences featuring midgets, guests shooting up mannequins with rifles and a subtle homosexual subplot (one of many), The Other Side of the Wind almost feels like a warped Hollywood version of the classic French classical music piece “Carnival of the Animals,” through it’s wild and unpredictable nature that results in a fascinating visual melody.

You can further thoughts on the film by Frank HERE. (@FrankFilmGeek)

I’m going to cheat a bit here and use my space this week to highlight not The Other Side of the Wind, but its critical and necessary companion film, They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead. As can be gathered from the reviews of my companions, The Other Side of the Wind is baffling and strange by design. They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead, also available on Netflix, is a documentary that explores the making, breaking, and forsaking of Orson Welles and his final film. The frustrated man of fragility and excess, a has-been living legend who sought to make another masterpiece which would serve as both his comeback and an autobiography of sorts. Told by those close to the production, it’s a fascinating and sometimes tragic look at the heartbeat and mindset of a tortured genius in his final, waning years. (@VforVashaw)

Next week’s pick: Network